Christian Dirce, 1897

Henryk Siemiradzki was a Polish Academic painter born on October 24, 1843. After studying painting in Russia and Munich he moved to Rome in his late twenties, where he would be known for his very large-scale paintings that rival Rubens in terms of sheer size. Siemiradzki (pronounced ShimiRADski) like many of his Russian-educated contemporaries, had a genius for multiple figure arrangement and use of natural light. Siemiradzki's attention to architectural and natural detail appears astounding from a distance, yet the way he paints detail is actually suggestive and emphasizes the appearance of texture over intricate detail.

In Christian Dirce above, Siemiradzki depicts a scene from Greek mythology portrayed in the Roman arena about Dirce, wife of the ancient ruler of Thebes, martyred by being tied to the horns of a bull. In this instance, by the title of the painting, it is a Christian woman being martyred in the same fashion as Dirce. Note the elaborate costumes and imposing body language of the Romans who look down at her, compared to the man and woman left of them who stare incredulously as if realizing the performance is real and not staged. Siemiradzki groups many of the figures in tight triangular arrangements, often with faces hidden behind other figures to heighten the drama and create a sense of group space taking over the composition. I like also how Siemiradzki use of hands to indicate the state of mind in key figures, from the guards watching along the right to the spectators above, and the Romans looking to the left. Note how the centurian has his arms folded behind his back to reveal his strict disciplined mind, while the emperor adjusts his robe to indicate his vanity. There seems to be a sense of pity in the beautiful woman who has been tortured, yet it is all for the sake of entertainment and the bull itself is also sacrificed in a pagan-like manner. Amidst the grandeur and lavish spectacle Siemiradzki comments on the relatively low regard for innocent human life and the perceived necessity to punish what is not tolerated or understood.

Curtain design for the Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Kraków, 1894

I love the musicality and flow of this painting. Look at the grace of the two women off to the right, hands joined, robes flowing, in a vertical arrangement that is breathtaking. And the ornate Oriental rug that covers the steps leading up to the very baroque architectural capriccio. Henryk contrasts a thunderclad sky to the left with a sunny and warm blue sky to the right, suggesting along with the figures the drama vs literary moral truth that all plays contain. This is a stunning concept considering it is only for the backdrop of a theatre in Poland. Sadly I could not find a larger image to display here for study. One thing is for sure, and that is Siemiradzki's work demands to be seen in person to appreciate its scale and full grandeur.

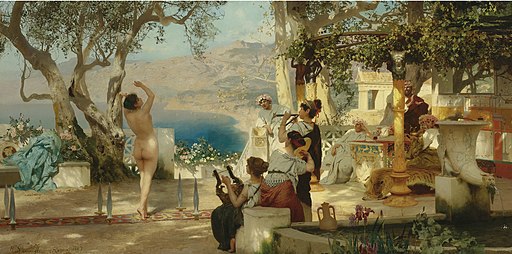

Dance Amongst Swords, 1881

Siemiradzki immerses us completely into this late afternoon musical idyll in the Mediterranean. I have never seen sun-dappled light portrayed quite this way in any type of mythological or capricious theme before. We seem to be transported in time and it feels very natural. This lovely dancer moves to the breeze of a sunny day and wind instruments with large swords pointed upward along a narrow path of rug. I'm not sure if this was a common ritual of Greek or Roman culture but the innocence and peacefulness of this scene clearly describes an ancient era long gone that we cannot fully relate to or understand, yet we marvel at its serenity and sensuousness. Freed from shame and religion, her feminine grace is not something to be sheltered from in a dark, dingy room with loud music and alcohol, but something open and unencumbered, free for anyone to celebrate and admire. Note how he places the dancer off center with the blue of the ocean and the mountains, surrounded by the canopy of trees, that provides a context and central theme to this wonderful painting. I love the vertical arrangement of the musicians, tightly knit in triangular fashion, leading the eye toward the dancer. A visual poem for the eyes.

Phryne at the Poseidonia in Eleusis, 1889

Phryne was a Greek courtesan from ancient Greece, her name in fact, literally meaning "toad" describing her warm complexion and a common nickname for courtesans and prostitutes from this era. Phryne was rumoured to be the model for Aphrodite of Knidos by famed Greek sculptor Praxiteles--the first nude sculpture of a woman. In this painting Siemiradzki depicts an ancient Greek agrarian ritual celebrating the coming of fertile crops that may have included a natural sort of hallucinogenic pre-LSD type of plant in the air that everyone got high from. At any rate, Phryne was known to have let her hair down and basically go skinny-dipping in the Aegean Sea. Her type of status as a prostitute was not the typical slave street woman but, as shown here, a wealthy, independent-minded and educated woman. Siemiradzki's spectators and their individualistic facial expressions are his unique genius. Again in dappled sunlight, this a natural setting for an unnatural anecdote that Siemiradzki immerses us into. Even the Greek temple atop the hill in the background, with flaming altar and some type of sarcophagus, is so real we don't even question it. The attention to costume here feels like a big budget film with an enormous cast of extras, in a scene of ancient Greece that seems like the everyday, not a grand spectacle. Siemiradzki breathes life into what usually can only be imagined as fantastic or mythological fantasy.

Roman orgy at Caesar's time, 1872

Siemiradzki's light is dark and absolutely beautiful here. Roman architecture against the twilight sky while revellers dance in a Roman pagan party. Here the partiers are too drunk for any kind of carnal activity, yet the dancing is fun and wild against the warm candlelight. What is curious about Siemiradzki is the lack of focal point or central characters...the theme is the activity itself and the context with Siemiradzki. Despite the connotation of this painting's title, what may be occurring in the shadows is what stimulates the imagination. Siemiradzki is conveying the frivolousness of a lost era in contrast to our own false morality which attempts to condemn while hiding secret passions behind closed doors, a question that begs us to ask which is the freer society, ultimately? Siemiradzki paints beautifully and his romantic notions of the ancient world are deep food for thought. The Classical world was not as stiff and boring as we may have imagined it...perhaps we are the boring ones.

Comments

Post a Comment